One of the greatest challenges of the project was creating a system that would allow both a PC player and a VR player to interact. While I had initially considered that this process would be as simple as dragging in two blueprints and adjusting the logic accordingly, this could not be further from the truth.

I had started by finalising the animations for the PC player, SPUD, and fully configuring their movement and animation in a third person project. I had then attempted to import a VR blueprint, however to my dismay, the two systems were entirely incompatible with each other. Getting the VR blueprint to work in the PC space proved unsuccessful, resulting in the creation of an interactive system with very little accurate documentation on the system online.

Most documentation on the topic indicated that local co-op was split screen only, and did not allow for the drastic differences in play style that my project requires. VR requires a full window in Unreal Engine in order to fully open and interact with the VR headset properly, and creating a game using the local co-op functionality was inaccessible for changing the player character blueprint to accommodate, so I opted to make a LAN multiplayer system that assigns the player blueprint based on if the player is the host or the client by making use of listen servers, which is a server that allows for a client to play directly on it in real time.

Session Creation logic, to automatically create or join a session

The system begins by placing the players into an empty map as soon as the game is open, and checking for nearby sessions. If none are found, it will create it’s own session and join it as a listen server, moving the player to the gameplay map and forcing the gameplay style to be VR. If one is found, then it will join that session, automatically travelling to the same map as the VR player, and spawn the new character on PC. This process essentially creates a LAN session, which the players can either join on the same computer by opening two sessions, or by opening two sessions on different computers connecting to the same network.

Character Spawning Logic

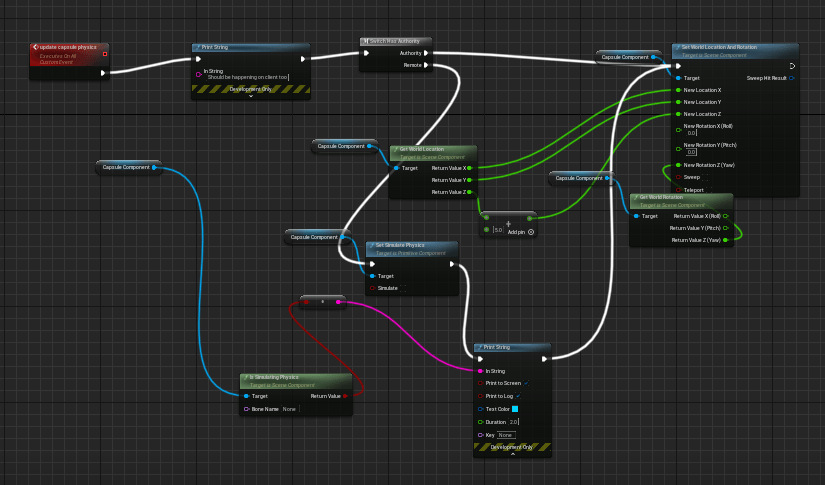

Once the players are both in the game, the main issue becomes replication. While both characters can be connected between separate instances, all objects are handled by the server only, meaning that when an object moves on the server, the client does not update. Setting up proper replication was difficult as it required for every updating object to be dealt with over both systems. In most cases, I set up replication to be ‘multicast’, to run first on the server, and then send any important updates to the client. All physics calculations are handled by the server, as well as animation, object movement, object activation code and VR player script. The only exceptions to this are the PC player’s inputs, which would call the replication mode of ‘run on server’, indicating that movement happens on that client and is then transferred onto the computer. A side effect of this system is that if the connection between the two computers is bad, it can lead to the PC player being out of sync with the VR player, however this is a rare scenario, as both players should be on the same network.

Replicated Code example. Events are set with “Multicast” replication in most instances.

After working out the multiplayer system, it was time to work on mechanics. I started by implementing the characters individually, and then combining them later on. For ADOS, this mostly involved creating a reference to SPUD, as well as handling how objects are held. Objects held by ADOS require the addition of a grab component in their blueprint, and this is handled by the game to link the component to the player’s hand and temporarily interrupt the physics of the game. I then continued with SPUD. SPUD required much more work than ADOS to perfect. Grab components do not work for third person characters, so I had to develop a secondary system for grabbing objects on PC, involving using a line trace, checking if the object has physics or an override, and then checking that ADOS is not already holding the object.

ADOS’ custom code

SPUD also required unique code, as not only are they able to grab and move as a player, but they can be grabbed by ADOS and thrown as a physics object. SPUD’s tail is a physics component with constraints to attach it to the player character. It has a grab component so that the ADOS can grab it. Once SPUD’s tail has been grabbed, they turn into a physics object, controlled server-side, still constrained to the plug. This means that the player can control the plug’s location in their hand, and swing SPUD around to throw them. SPUD’s velocity is checked once they are let go, and if it is less than 5 units in any direction, then control is given back to the PC player and they can move around from their new location.

SPUD’s full code

Snippets of SPUD’s code, including plug logic, resetting player movement and picking up objects.

Another difference between the two characters is their movement systems. ADOS moves by teleporting, which involves placing a VR Navigation mesh to calculate which areas are teleportable, while SPUD moves by standing on any objects that have a “block” collision setting. This meant that all terrain had to be available to each character, only when necessary.

Once interaction logic had been implemented for the players, I implemented the logic for other objects, including doors, physics and VR buttons, sockets and cardboard boxes, each requiring double the playtesting to ensure that they worked in both mediums. Finally, I created the blueprints for tennis balls and glass flasks, which both have no functional purpose to the game other than providing fun methods of interaction between the two players. Tennis balls are regular physics objects with substantially more bounce that the players can use to play catch with each other, and the glass flasks acts as physics objects, except smashes with a sound and particle effects when hitting something with too high a velocity.

Tennis Ball Code. Other interactable blueprints are similar.

Playtesting was an integral phase of this project, with player feedback creating many of the changes to the systems. VR players found that unlocking doors in-game was impossible, as the VR player’s hands had no blocking component, however this was not an issue, as the players could teleport through doors, regardless of if they were locked or not. VR players also noted that SPUD’s cord was too long, making throwing both difficult and clunky. PC players found that physics objects would sometimes clip out of bounds, especially smaller ones like keys and tennis balls. The help of player feedback, these issues were resolved.

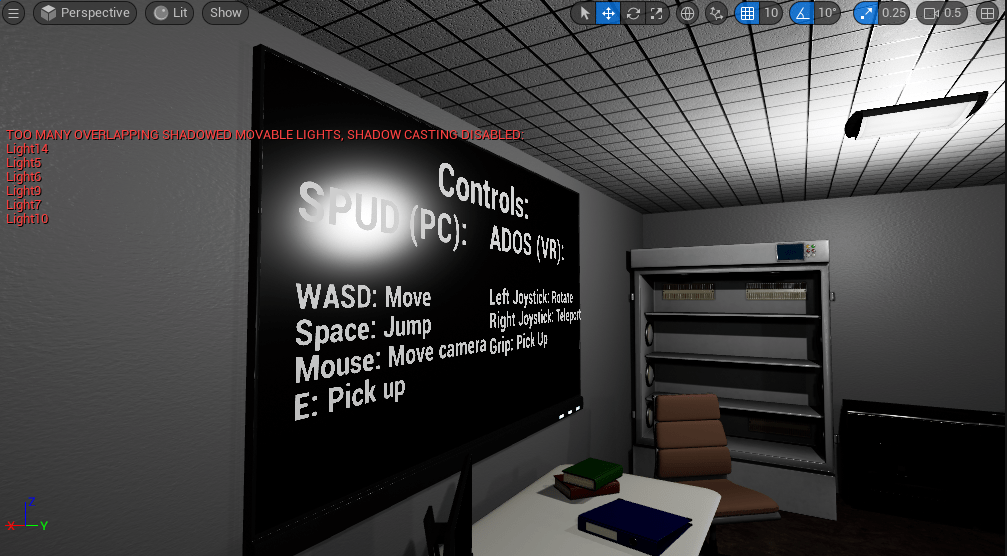

VR players made an interesting discovery when it came to controls. While I have personally played VR games for several years now, many of my players found that they did not know the controls. I was unable to see this as an issue without peer review, as VR controls were a control scheme that I was used to, however many of my peers that tested the game had either never played a VR game before, or they have had extremely limited experience with VR games, and thus didn’t know the controls. It was suggested that the controls were presented to the player in the starting room, which is a suggestion that I took on board. I created a controls board, outlining all necessary controls for the game that can be viewed by the VR player by looking around the room. This is presented here, as the VR player has plenty of interactable objects in the room to get accustomed to the controls, and the controls can be viewed without any input other than looking around the room.

Controls for both players

The creation of the base system was the section that took the longest, and the largest section of the project. What I had initially considered to be easy took up much more space in the project than was initially intended, due to the complicated nature of local multiplayer with two different play styles, as well as essentially coding every system twice to fit with both playstyles. This unfortunately meant I had to reconsider the scope of my project as a whole. I ended up cutting back the intended number of levels being made due to time constraints, as well as how many assets I would make for the game as a whole. I ultimately decided I would make as many assets as possible, prioritising any assets used for an interaction other than set design.